Acute Inflammation with a Focus on Sepsis

General information

The theme of SensUs 2022 is acute inflammation in intensive care with a focus on sepsis. According to the World Health Organization, sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. It causes 11 million deaths each year and affects an estimated 49 million people worldwide.[2] According to experts, the diagnosis of sepsis is often set too late as the symptoms arise when organ injury has already occurred, hence the millions of deaths. Sepsis is one of several acute inflammatory responses; others can be caused by injurious agents such as allergens, toxins, burns, and frostbite.[3] Clinically, acute inflammation is characterized by five cardinal signs: redness, increased heat, swelling, pain, and functio laesa (i.e. loss of function). It may be regarded as the first line of defense against injury, releasing signaling molecules such as cytokines and chemokines to assist in healing the body and returning to homeostasis. [4]

Interleukin (IL)-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine with a wide range of biological activities. It induces pro- and anti-inflammatory reactions and is rapidly induced in the course of acute inflammatory reactions. IL-6 is produced by lymphoid and nonlymphoid cells and helps regulate immune reactivity, the acute phase response, inflammation, oncogenesis, and hematopoiesis. Studies have shown that IL-6 appears to be both a marker and mediator of sepsis and persists in the plasma much longer than other proinflammatory cytokines.[5] Therefore IL-6 serves as a valuable biomarker for the early detection of sepsis.

History of Sepsis

The oldest report that associates sepsis with wounds goes all the way back to a discovery by Edwin Smith. In 1826 he found a papyrus in Luxor, Egypt, which was written around 1600 BC. This papyrus seemed to be a copy of an even older manuscript written around 3000 BC. In this manuscript, 48 cases of traumatic lesions between wounds, fractures, and dislocations are mentioned. Clear references to fever as a secondary phenomenon in the wound – with emphasis on the fever as a part of the monitoring of the patients’ evolution - are found in five out of the forty-eight references. Thus, without being familiar with the concept of infection or inflammation, these Egyptian physicians were able to identify some clear signs of what we know nowadays as local suppuration and systemic infection. [6][7][8]

The first reported use of the word sepsis (σηψις) is in a poem of Homer in the Iliad, where it is a derivative of the word sepo (σηπω), which translates to “I rot”. Yet, the first use of sepsis in a medical context can be found in the Hippocratic corpus, written around 400 BC. The use of this word was related to the phenomenon discovered by the Egyptians. Hippocrates described sepsis as a dangerous odiferous biological decay that could occur in the body. Furthermore, it was believed that this decay took place in the colon and from there “dangerous principles” were released, which could cause “auto-intoxication”. Hippocrates was the first one to try and find antisepsis properties and potential medicinal compounds.[6][9][8]

In the nineteenth century, large growth in the knowledge on the origin and transmission of infectious diseases occurred. One of the physicians who contributed significantly to this development was Ignaz Semmelweiss (1818-1865). He was a physician in Vienna, Austria. In 1841, while working on a maternity ward in a hospital he noticed that there was a high rate of death from childbed fever. Nowadays this is also known as puerperal sepsis. He made the observation that women whose deliveries were assisted by midwives had a significantly lower percentage of infection (2%) than deliveries assisted by medical students (16%). Back then, the medical students practiced both autopsies and childbirth deliveries on the same day without washing their hands. When one of Semmelweis’ colleagues died of an infection, Semmelweis made the connection between the medical students, the deliveries, the autopsies, and puerperal sepsis. Semmelweis’ comment on this situation was “The fingers and hands of students and doctors, soiled by recent dissections, carry those death-dealing cadaver’s poisons into the genital organs of women in childbirth”. When a handwashing policy was implemented, the rates of puerperal sepsis dropped to under 3%.[9][7][8]

In 1964 Dr. Edward Frank from Boston published a management strategy for septic shock. This strategy consisted of continuous monitoring of systemic arterial pressure, central venous pressure, cardiac output, urinary output, blood volume, blood chemistries, gases, pH and electrolytes. Some of these are still used nowadays, such as blood monitoring and urinary output. Aided by the discovery of antibiotics by Alexander Fleming, it was also recommended to find the cause of the infection.[10]

References

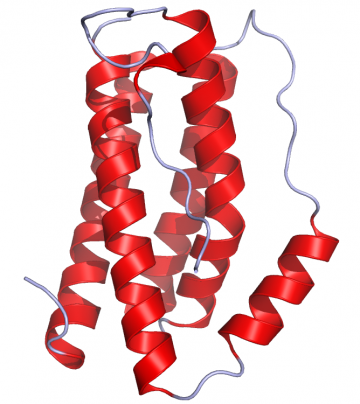

- ↑ Crystal structure of IL-6 as published in the Protein Data Bank rendered in Pymol (PDB: 1ALU), 2006, Ramin Herati

- ↑ WHO - Health topics - Sepsis, WHO, 2021, https://www.who.int/health-topics/sepsis#tab=tab_1

- ↑ Acute Inflammatory Response, StatPearls Publishing LLC, 2020, Hannoodee, Sally Nasuruddin, D. N.

- ↑ Concise Pathology (3rd ed.), Appleton & Lange, 1997, Chandrasoma, P., & Taylor, C. R.

- ↑ Interleukin-6. Critical Care Medicine, 33(12 Suppl), S463-5, 2005, Song, M., & Kellum, J. A. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000186784.62662.a1

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The History of Sepsis from Ancient Egypt to the XIX Century, (M. C. F. P. E.-L. Azevedo (Ed.); p. Ch. 1). IntechOpen, 2012, Botero, J. S. H., https://doi.org/10.5772/51484

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 The last 100 years of sepsis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 173(3), 256–263, 2006, Vincent, J.-L., & Abraham, E., https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200510-1604OE

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Sepsis History, https://www.news-medical.net/health/Sepsis-History.aspx, 2018, Ryding, S.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Sepsis and septic shock: a history. Critical Care Clinics, 25(1), 83–101, viii, 2009, Funk, D. J., Parrillo, J. E., & Kumar, A., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2008.12.003 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Arti9" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ The History of Sepsis Management Over the Last 30 Years. Elsevier, 15(2), 116–117, 2014, Zehava L., N., https://daneshyari.com/article/preview/3235901.pdf