Difference between revisions of "Traumatic Brain Injury"

Techsensus (talk | contribs) m |

Techsensus (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

GFAP is a protein found in the glial cells of neural tissue. Glial cells are non-neuronal cells that provide physical and metabolic support to neurons. Blood biomarker levels of GFAP reflect acute injury to brain tissue since the biomarker levels increase strongly and fast within hours after the trauma occurred. Therefore, it has potential use in the emergency unit and intensive care unit, directly after the TBI. Furthermore, the biomarker persists for an extended period with a half-life of 48 hours, making it a favourable biomarker to use in both the acute and subacute phases of injury. The concentration of GFAP peaks at about 20 hours after the injury. Reference serum levels of GFAP range from 0.02 — 0.35 𝜇g/L and the cut-off value of a negative CT scan for GFAP is 0.35 𝜇g/L.<ref name="Arti5">Papa, L., Brophy, G. M., Welch, R. D., Lewis, L. M., Braga, C. F., Tan, C. N., Ameli, N. J., Lopez, M. A., Haeussler, C. A., Mendez Giordano, D. I., Silvestri, S., Giordano, P., Weber, K. D., Hill-Pryor, C., & Hack, D. C. (2016). Time Course and Diagnostic Accuracy of Glial and Neuronal Blood Biomarkers GFAP and UCH-L1 in a Large Cohort of Trauma Patients With and Without Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Neurology, 73(5), 551. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0039 </ref> | GFAP is a protein found in the glial cells of neural tissue. Glial cells are non-neuronal cells that provide physical and metabolic support to neurons. Blood biomarker levels of GFAP reflect acute injury to brain tissue since the biomarker levels increase strongly and fast within hours after the trauma occurred. Therefore, it has potential use in the emergency unit and intensive care unit, directly after the TBI. Furthermore, the biomarker persists for an extended period with a half-life of 48 hours, making it a favourable biomarker to use in both the acute and subacute phases of injury. The concentration of GFAP peaks at about 20 hours after the injury. Reference serum levels of GFAP range from 0.02 — 0.35 𝜇g/L and the cut-off value of a negative CT scan for GFAP is 0.35 𝜇g/L.<ref name="Arti5">Papa, L., Brophy, G. M., Welch, R. D., Lewis, L. M., Braga, C. F., Tan, C. N., Ameli, N. J., Lopez, M. A., Haeussler, C. A., Mendez Giordano, D. I., Silvestri, S., Giordano, P., Weber, K. D., Hill-Pryor, C., & Hack, D. C. (2016). Time Course and Diagnostic Accuracy of Glial and Neuronal Blood Biomarkers GFAP and UCH-L1 in a Large Cohort of Trauma Patients With and Without Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Neurology, 73(5), 551. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0039 </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == History of TBI == | ||

| + | === Pre-historic period === | ||

| + | TBIs play an important role in the evolution of humans. Studies of skeletons from the mesolithic period (c. 7000 BC) suggest an inverse relationship between the risk of skull fracture and the progress of civilization. The palaeolithic period is a period in prehistory that occurred over a million years ago. In those times, man's predecessor was a semi-erect hominid now named Australopithecus africanus; a damaged skull from this species found in South Africa reveals the first evidence of brain injury.<ref name="Arti6">Rose, F. C. (1997). The history of head injuries: An overview*. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 6(2), 154–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647049709525700 </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of the earliest methods used for treating TBI is called Trepanation. Trepanning, also known as trepanation, is a surgical intervention in which a hole is drilled or scraped into the human skull. The earliest evidence of trepanation performed by the man himself appears in the Neolithic period. The primary theories for the practice of trepanation in ancient times include spiritual purposes and treatment for epilepsy, headache, head wound, and mental disorders. | ||

| + | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 18:24, 4 December 2022

General information

The theme of SensUs 2023 is Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). It is often stated in the literature that TBI is a silent epidemic with an estimated 64–74 million new cases presenting each year.[2] The impairments suffered by many TBI patients, such as memory loss, cognitive dysfunction, or behavioural disturbance, are often not visible. The economic and social impact is considerable, with an estimate of direct medical expenditures and indirect costs (e.g., loss of productivity) attributed to TBI exceeding $60 billion in 2000 in the USA. TBI is defined as an alteration in brain function, or other evidence of brain pathology, caused by an external force.[3] The severity of injury in TBI is classified as mild, moderate, or severe with mild TBIs being the most common.[4] Alteration in brain function can be manifest by loss or decreased level of consciousness, alteration in mental state, incomplete memory for the event, or neurological deficits. Examples of external forces include the head striking or being struck by an object, rapid acceleration or deceleration of the brain, penetration of the brain by a foreign object, and exposure to forces associated with blasts.

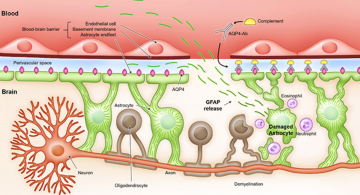

GFAP is a protein found in the glial cells of neural tissue. Glial cells are non-neuronal cells that provide physical and metabolic support to neurons. Blood biomarker levels of GFAP reflect acute injury to brain tissue since the biomarker levels increase strongly and fast within hours after the trauma occurred. Therefore, it has potential use in the emergency unit and intensive care unit, directly after the TBI. Furthermore, the biomarker persists for an extended period with a half-life of 48 hours, making it a favourable biomarker to use in both the acute and subacute phases of injury. The concentration of GFAP peaks at about 20 hours after the injury. Reference serum levels of GFAP range from 0.02 — 0.35 𝜇g/L and the cut-off value of a negative CT scan for GFAP is 0.35 𝜇g/L.[5]

History of TBI

Pre-historic period

TBIs play an important role in the evolution of humans. Studies of skeletons from the mesolithic period (c. 7000 BC) suggest an inverse relationship between the risk of skull fracture and the progress of civilization. The palaeolithic period is a period in prehistory that occurred over a million years ago. In those times, man's predecessor was a semi-erect hominid now named Australopithecus africanus; a damaged skull from this species found in South Africa reveals the first evidence of brain injury.[6]

One of the earliest methods used for treating TBI is called Trepanation. Trepanning, also known as trepanation, is a surgical intervention in which a hole is drilled or scraped into the human skull. The earliest evidence of trepanation performed by the man himself appears in the Neolithic period. The primary theories for the practice of trepanation in ancient times include spiritual purposes and treatment for epilepsy, headache, head wound, and mental disorders.

References

- ↑ Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein in Blood as a Disease Biomarker of Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders. Front. Neurol., 17 March 2022, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2022.865730/full#F1

- ↑ Rattani, A., Gupta, S., Baticulon, R. E., Hung, Y. C., Punchak, M., Agrawal, A., Adeleye, A. O., Shrime, M. G., Rubiano, A. M., Rosenfeld, J. V., & Park, K. B. (2019). Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurosurgery, 130(4), 1080–1097. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.10.jns17352

- ↑ Menon, D. K., Schwab, K., Wright, D. W., & Maas, A. I. (2010). Position Statement: Definition of Traumatic Brain Injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91(11), 1637–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.017

- ↑ Iaccarino, C., Gerosa, A., & Viaroli, E. (2021). Epidemiology of Traumatic Brain Injury. In S. Honeybul & A. G. Kolias (Eds.), Traumatic Brain Injury. Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-78075-3_1

- ↑ Papa, L., Brophy, G. M., Welch, R. D., Lewis, L. M., Braga, C. F., Tan, C. N., Ameli, N. J., Lopez, M. A., Haeussler, C. A., Mendez Giordano, D. I., Silvestri, S., Giordano, P., Weber, K. D., Hill-Pryor, C., & Hack, D. C. (2016). Time Course and Diagnostic Accuracy of Glial and Neuronal Blood Biomarkers GFAP and UCH-L1 in a Large Cohort of Trauma Patients With and Without Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. JAMA Neurology, 73(5), 551. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0039

- ↑ Rose, F. C. (1997). The history of head injuries: An overview*. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 6(2), 154–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647049709525700